Cultural diplomacy: The linchpin of public diplomacy

Report of the advisory committee on cultural diplomacy: US department of state

The report of the advisory committee on cultural diplomacy, which was published by the U.S. department of state in 2005, seeks to advise US secretary of state on how to employ cultural diplomacy in the most effective way possible.

In order to practice effective cultural diplomacy the report recommends the US secretary of state to listen to the recipients in other countries and engage themselves with “curators” and writers or filmmakers. The report highlights America’s lack of use of cultural diplomacy, moreover that its image has been damaged by events such as the invasion of Iraq and scandals about the abuse of prisoners in Abu Ghraib. Furthermore, it points out that the US needs to reconstitute its “trust and credibility” within the international community with culture, rather than with military and economic power to influence others abroad. “Cultural diplomacy reveals the soul of a nation”, but the US only employs it when they are at war, therefore the report advises the US to create an effective cultural diplomacy in order to maintain the security of the country. One of the many recommendations for the US secretary of state from the report on how to achieve its goals is the “international exchange of persons, knowledge and skills”. The people who participate in such exchanges “carry to other nations information, knowledge and attitudes” and in reverse they bring those back to their own countries and this can only be achieved through personal experience and personal influence, which helps to sell a better image of the US abroad. Influential and important politicians from the past and today have all experienced such exchange programs.

However, the reports criticized the US that they do not cultural diplomacy enough, moreover after the cold war cuts have been made, which led to the closures of many cultural centres and libraries. Additionally, between 1995- and 2001 the attendees of the exchange programs decreased from 45000 to 29000, which left an enormous gap in the use of cultural diplomacy.

Globalization has changed the world and it had a massive impact on the procedure of diplomacy. Diplomacy has now taken different forms and different actors also play an important role, diplomats are no longer the only ones on diplomatic missions, also non-state actors, such as Ngo´s and celebrities engage themselves on those missions.

Due to the rise of new economic powers and the new media, traditional diplomacy is facing a challenge of legitimacy and efficiency. Celebrities have now become vital actors in supporting and raising consciousness about humanitarian issues, as well as negotiating with head of states.

Celebrities have long been involved in varying political and humanitarian causes. However, since Andrew Coopers, a professor of political science at the University of Waterloo, intriguing work about celebrity diplomacy, academics have begun to take a deeper look into the involvement of celebrities in International Relations as a form of diplomacy. In his book cooper presents an interesting concept and primary examples of the phenomenon. He argues that anyone can be a diplomat; however celebrities are a specific group that can embrace the role of the diplomat. The message which these individuals deliver is often informal in its nature and they are no experts in these fields with any formal training, also they use the new media and concerts, such as Bob Geldofs Live8 concerts to raise awareness.

Cooper argues that the influence of celebrities on global issues must be appreciated and recognized on a deeper level; furthermore advocates of celebrity diplomacy argue that this concept has immense potential and it draws attention and awareness of a complex set of global concerns to wider audiences, which might go unnoticed. Celebrities of any kind, like Movie stars, musicians or athletes have become rising diplomatic actors in promoting issues such as poverty, climate change, access to fresh water and human rights.

Unlike diplomats, stars like Angelina Jolie, Mia Farrow, Bono and George Clooney are taking action and they have become determined advocates to end the world’s poverty and misery.

For example, actress Mia Farrow has used the media as an open and effective tool to put pressure on the international community in order to intervene in Darfur, her deployment led to Sudan’s formal acceptance of UN peacekeepers in the conflict zone.

As a UNHCR goodwill Ambassador, Angelina Jolie is one of the most respected, important and influential celebrity activists. Her work has been crucial for the UNHCR, in both increasing donations and increasing awareness. With her status and her engagement in global issues she able to discuss humanitarian issues with politicians, policy makers and world leaders.

Also, George Clooney plays an important role in this new form of diplomacy as a UN Messenger of Peace. Clooney has donated millions of dollars in order to stop the genocide in Sudan and he also appealed to the UN Security Council to help stabilize the region.

However, the leading celebrity diplomat out of all of them is musician Bono, who worked closely with international leaders in the G8 summits, lobbying for debt relief in Africa.

Even though the world listens and pays attention when celebrities talk, which makes them more effective than traditional diplomats, there still is criticism from within the diplomatic arena. The critic’s state that celebrities have no knowledge in this domain and therefore are not qualified enough to be effective.

In spite of all the critiques, celebrity diplomacy has been proven very successful and effective in international affairs. Therefore, it needs to be taken serious, since they do a better and more effective job the “professional” diplomats.

http://www.learcenter.org/pdf/celebritydiplomacy.pdf

http://www.cigionline.org/articles/2007/12/celebrity-efforts-will-redefine-diplomacy

http://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/index.php/about/bio_detail/andrew_f_cooper/

Citizen diplomacy is the concept where the individual has the right, perhaps even the responsibility to help form its countries foreign relations. Everybody can represent their nation and become a citizen diplomat; they can be students, artists, business people, teachers, athletes, humanitarians or musicians. Their role and responsibility is to engage themselves with the rest of the world in an important, equally and favorable dialogue.

In the globalized world that we live in today people experience their most lasting impressions through personally made experiences, such as travelling abroad. Therefore, citizen diplomacy is a powerful tool in defining one’s own nation to the rest of the world. Citizen diplomacy has the potential to create a group of individual relationships to maintain goodwill when formal diplomacy undergoes disruptions. Historically, this kind of people-to-people interaction was almost impossible through the enormous distances, however in today’s world with the rise of the internet and collapse of distances and increased travel more individuals on the international stage are able communicate and influence one another. For example, Joseph Nye believes that the best way for a country to sell its story to a foreign country is the use of citizen diplomacy, because “selling a positive image is often best accomplished by private citizens”.

The Nigerian government adopted “citizen diplomacy” in 2007, which was based on the ideas of the former foreign affairs minister, Chief Ojo Maduekwe. Nigeria seeks the support of Nigerians at home and in Diaspora, in order to help to develop the country economically and politically. Citizen diplomacy in Nigeria is construed from a different angle of understanding; this means that its foreign policy will be focused on the Nigerian citizens at home and abroad. The foreign minister argues that they are not shifting away from the traditional approach to foreign relations, however that they have “rebranded” this tool and that the focus is more on the citizen. In this sense, citizen diplomacy for Nigeria is a mechanism to protect the “image and integrity” of Nigeria and react against nations which are hostile and who label them as corrupt.

http://onlineresearchjournals.com/ijopagg/art/59.pdf

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/05/opinion/05iht-ednye.html

http://diplomacyworld.wordpress.com/2010/06/20/lets-define-citizen-diplomacy/

Report to be accessed under: http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=SPEECH/08/494&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en

The report presents the Vice President’s of the European Commission, Margot Wallstrom’s, speech at the Georgetown University, the purpose of which was to state the role of public diplomacy (PD) in the European Union’s (EU) relations with non-member states.

Wallstrom specifically highlights the relation between the EU and the United States on the platform of public diplomacy, as both honour the same democratic values in theory but use different approaches in practice.

The report also emphasises, that nowadays the concept of public diplomacy needs to be “refreshed”. If it is to work effectively, factors such as communication in a globalised world, modern technology and reaching many complex networks of individuals have to be considered while utilizing PD’s tools.

Furthermore, it expresses the extreme importance for the EU to realize the shift in power and decision-making and in its efforts of tackling the most important global issues, to try to “go local“. The latter is a crucial public diplomacy element as one must remember that it is about building relations with foreign and not domestic publics.

Wallstrom also recalls the necessary components of a modern PD strategy according to Nicholas Cull, such as attentively “listening and responding” to citizens‘ opinions, connection of practice with policy, “going local”, credibility etc. and relates them to EU’s external affairs.

It is beyond a dispute that Wallstrom is correct in claiming that PD must adapt to the changing world. Also, all the components she mentions are vital for this adaptation’s success however, it seems that the report does not explore the role of public diplomacy in EU’s policy but rather tries to explain how does the EU respond to all the requirements of the modern PD structure as according to her and Cull. Thus, it appears as a persuasion that EU is doing excellent in fulfilling all the necessary PD-related assignments more than stating what is the specific aim that EU aspires to achieve via the use of PD‘s tools. For comparison, what I have expected from the speech, was identification of some PD stepts that EU is taking or must take soon in order to deal with some current global policy issues. For instance, it could be a development of a European Strategy of External Cultural Policy in response to a strategic vision of a role of culture in external relations as was once proposed by Slovenia during its presidency in the EU.

Nevertheless, the report still touches upon a few key issues in PD, probably the most crucial being the need for credibility. Its importance relates to the fact that PD’s messages recipients often look at the information through the prism of the messenger and cannot differentiate between a mere propaganda and an attempt to create a “partnership” with the public. Fortunately for the EU, its position as a world leader in providing world’s development aid and fighting climate change increases it legitimacy.

EU also manages to create a link between its PD strategies and its defined policy objectives thus allowing the public to understand them and engage in a mutual dialogue.

Also, thanks to diversity of member states, EU is better prepared to target communication with states outside the EU.

Despite those undeniable attributes, some sources still show that “brand Europe” is far more popular than “brand EU“ as it is comonly associated with all the historical and cultural heritage of the Old Continent. In the report it can be seen that EU has adopted a long-termn approach and is patiently but actively pursuing its goals while trying to reflect what it is and what it stands for rather than what it aspires to be which hopefully will improve its reputation with time. This may be a right path for the EU if considering for instance Anholt’s view on building a brand to increase its credibility.

All in all the report could have focused more on what EU is willing to build and how it s going to meet its targets. Instead it presented more of a strategic outreach to the US thanks to which it will be able to improve its image in the eyes of American students by emphasizig the goals in common.

Public Diplomacy=Propaganda?

Public Diplomacy is aimed at informing foreign publics, its mission is the achievement of national interest by understanding, informing, engaging and persuading foreign audience, Public Diplomacy is as much about a process by which both sides learn, as it is to convince someone. However, there seems to be a disagreement between scholars what public diplomacy is, since some find a connection between public diplomacy and Propaganda.

Berridge, for example, relates those two concepts as follows, “Propaganda is the manipulation of public opinion through the mass media for political ends, whether it is honest or subtle or not.” Furthermore he states that Public Diplomacy is the modernised version of white Propaganda, which is aimed at influencing public opinion. In his opinion Public Diplomacy is just a euphemism for Propaganda, because governments who carry out Propaganda cannot call it Propaganda, because of its associations with something negative, evil and lies.

However, his opponent Jan Melissen does not completely agree with the critics of Public Diplomacy. He distinguishes the two terms by their concept of communication, he argues that “Public Diplomacy is a two- way street, it is similar to Propaganda in the sense of trying to persuade People what to think, however the main difference is that Public Diplomacy also listens to what people have to say, which is not the case with Propaganda”.

Joseph Nye also criticises the opponents of Public Diplomacy, he says that those who think that Public Diplomacy is just a euphemism of Propaganda misunderstood the whole concept of it. Public Diplomacy is compare to Propaganda about building relationships between nations it is used to create a better political environment. He furthermore states in his article that “the world of traditional power politics was typically about whose military or economy would win, however in today’s information age, politics is also about whose “story” wins. In current times the strongest element of Power is Public Diplomacy. In addition he argues that reputation was always important in world politics, but credibility has become more vital because of a “paradox of plenty”, therefore politicians should use more often soft power rather than hard power, since it is more effective.

Reflecting the definitions of Public Diplomacy and Propaganda the question arises if those two concepts are the same thing. There are indeed some who would argue that Public Diplomacy has the same intentions like Propaganda, both concept´s purpose is to narrow and close the minds of the people, by trying to tell them what to think. However, there will probably never be a universal agreement on both concepts, since both are difficult o define.

Berridge. G.R. (2010) Diplomacy: Theory and Practice

Melissen, J. (2005) The New Public Diplomacy

When Adolf Hitler occupied European countries and practiced holocaust to make more lebensraum (living space) for Nazi übermenshen (overlords) he certainly did know that it helped to create one of the most powerful and the richest people in the world – George Soros.

One the physical laws says: ”The subject stays in quite position or in stationary movement until it is pressured by external forces to change its status”. Sometimes it is possible to apply technical rules in politics. Possibly, without holocaust George Soros would stays in nativeHungaryand worked all the life for salary 2000 forint/month (equivalent approx $50) But Sores had had to move because of necessity for survival. He successfully moved toLondonand studied at London School of Economics. Later used knowledge obtained inLondonagainst this country when became one of the most dangerous sharks in ocean of global capital. One Chinese military report ranked him just behind Osama bin Laden because in ‘financial war’ against theUnited Kingdomin 1992 broke this country and the Bank of England had to pay millions ofGBPfor wasteful operations.

In the United States Soros proved that theories both of Adam Smith, father of liberal economy and Friedrich Hayek, who lectured at London School of Economics approximately at the time of Soros’ study (may be he was Soros’ professor) work and the United States’ market economy is the environment when everybody has an opportunity to become rich. Soros has become the billionaire currency trader, philanthropist and one of the most important people of public and cultural diplomacy. He helped with his millions to build a new education infrastructure inHungaryand other East European countries which after falling ofBerlinwall needed new millions to throw Marxism and Leninism to dust bins and to build a market economy that helped Soros to become an important meacenas. Maecenas is a person named as an honour for real person from ancient Roma -Gaius Maecenas, a rich patron of culture and friend and political advisor of Caesar Augustus.

Nevertheless, public and cultural diplomacy need also maecenases such as Soros, Ted Turner, the CNN founder who as a generous patron has given $1 billion to start the UN Foundation and support for UNICEF, Bill Gates and other post-modern diplomats. In the other hand critics of these celebrity diplomats argue that they intervene and interfere not only to the economies of states but also into international relations and security. For example, some politicians inRussiasee Soros as an agent of Western policy, but he is much more a “stateless statesman” who funded UN operations to “saveSarajevofrom Serbian fascism” (Khana, 2011, 41-44). Globalization increase gap between rich and poor and financial support of these post-modern diplomats is very necessary to implement some foreign aid programmes and to support the people who need financial help.

References:

Khanna,P. (2011). How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance, Random House,New York

Prince Harry is an important celebrity diplomat of theUnited Kingdom. He proved it during his public and cultural diplomacy mission in hisCaribbeantour in March 2012.

Not only Harry but all the royal family is an important asset for theUKpublic and cultural diplomacy. For example, Prince Harry was sent to the Caribbean at the beginning of March 2012 by the Queen to improve international relations between the UK and Caribbean countries. It plays an important role to make theUKmore attractive inCaribbeancountries (Lydall, 2012, 3). The Royal Family is the asset for promotion of theUKabroad. TheUKlost colonies but the Commonwealth create framework of collaboration between theUKand former colonies. The queen as a head of the Commonwealth plays a very important role in communication with public abroad.

Public and cultural diplomacy play very important role in promotion theUKabroad, improvement of nation branding and achieving the goals of foreign policy. Improvement of nation branding means to improve perception about theUKand increasing of attraction of the country abroad by communication a fresh image of theUK.

The aim of the British public and cultural diplomacy is to improveBritain’s image abroad and at home, to promote theUK’s values, to make it more attractive for foreign audiences and to shape public opinion in accordance with the national and business interests of theUnited Kingdom.

According to Cambon, “Diplomacy will always have ambassadors and ministers; the question is whether it will have diplomats” (Cambon cited in Khana, 2011, 30). Nowadays, both traditional diplomacy and public and cultural diplomacy are very important to achieve foreign policies goals. Celebrity diplomats are important, useful and necessary at the present time because they possess prestige which helps to achieve success in diplomacy. On the other hand, traditional diplomats play also very important role in international relations at the present time. For example, US ambassador Richard Holbrooke, known as “The Buldozer” successfully brought Serbs to the negotiation table to end conflict in former Yugoslavia in 1995 (Khana, 2011, 35). He played also an important role in theUSdiplomacy during the Afghan war. When Holbrooke died on13 December 2010, Hilary Clinton proclaimed at his Memorial that he understood that in the end the only solution of conflict inAfghanistanwas political (Cowper-Coles, 2011, 275).

References:

Cowper-Coles,Sh. (2011). Cables from Kabul: The Inside Story of the West’s Afghanistan Campaign, Harper Press, London

Khanna,P. (2011). How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance, Random House,New York

Lydall,R. (2012). “Hugging Harry the Diamond diplomat.”, The Evening Standard, March 7, 3

Due to the accelerating speed of globalization and the communications revolution the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs has recognised the importance of grabbing the prominence of public and cultural diplomacy to promote a more positive image of Denmark abroad. Reasoned the major diplomatic setback Denmark experienced as a result of the Cartoon Crisis, Denmark has assigned greater priority to the MENA-region as a crucial strategic target of PCD.

The report, ‘Danmark i Dialog med Verden’ (Denmark in Dialogue with the World) provides a range of examples of public and cultural diplomacy initiatives around the world with a particular focus on the MENA-region. A special emphasis on cooperation with non-state actors such as NGOs, companies, interest-organisations and the media is articulated.

In concordance with Nicholas Cull’s statement that action speaks louder than words[1], the report attempts to draw attention to Denmark’s top position among donors of development assistance to promote an image of Denmark as a development assistance role model. This can prove to be a rather effective strategy as Denmark as of 2009 was among the only five nations who have met the International Aid Target of 0.7% of GNP.

The report promotes the necessity of nation branding as it aims to project its ‘50 years of participation in peacekeeping operations and defense efforts, a top spot on the quantity and quality of development assistance and a place in the first ranks in the struggle for human rights are the main motives in the image of Denmark’s global engagement[2].’This constitutes a part of the idea of ‘borderless responsibility’ which attaches importance to stability, peace and democracy aimed at international organizations, opinion-makers, decision-makers and the broad public in selected countries. It is obvious that the report finds its inspiration domestically. Because Denmark’s job market model flexicurity (a contraction of the English words ‘flexibility’ and ‘security’) has been promoted as the road to economic growth and employment by the European Commission, Denmark has used this as a public diplomacy tool in Greece in order to generate better acquaintance with Danish experiences and expertise in this area. The Danish welfare model is something it has in common with other Scandinavian countries but Denmark has been more eager than for instance Norway and Sweden to market this image. Hence, it can be argued that the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs truly comprehends the importance of congruence between words and deeds adding enhanced credibility to the country’s efforts abroad.

Project Hip Hop Palestine is directly aimed at resurrecting the image of Denmark in Palestine where 59% of the population view Denmark as an enemy of Islam and only 4% believe that the Danish government handled the cartoon crisis appropriately[3]. The initiative is one among many and is characterised as ‘offbeat’ remaining apolitical but cultural in nature where ‘intercultural dialogue’ often occurs in the rhetoric. To enhance this intercultural dialogue, the report and its Palestinian collaborators have in particular appreciated the credibility that Danish youths with Palestinian backgrounds bring to the dissemination of information about Denmark and hence these cultural non-state ambassadors comprise an essential part of the project. The primary goal of the project, which has also involved song contests, has been to raise the prospects of Palestinian participation in the Eurovision Song Contest. The success of the project has been so highly-profiled that even Israeli media has picked up on it.

Project Hip Hop Palestine is part of a larger initiative called Det Arabiske Initiativ (The Arabian Initiative) whose purpose it is to create a foundation of strengthened dialogue (two-way communication), understanding and cooperation between Denmark and the Arab world to support ongoing local processes of reform.

Because Denmark as a nation initially failed to understand the implications of the Cartoon Crisis, this report constitutes a crucial effort to rectify that mistake. Denmark has understood that it’s success as a nation, also domestically due to its large Muslim population, is dependent on its image abroad leading to an appreciation of mutual understanding and cooperation across borders.

[1] N. J. Cull, ‘Public Diplomacy: Seven Lessons for its Future from its Past’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2010, p. 14.

[2] This part is translated.

[3] Independent Media Review Analysis, http://www.imra.org.il/story.php3?id=28497

At the height of the Cold War years, “Jazz Diplomacy”, proved to be the most powerful tool of the United States to diminish both the credibility and appeal of Communism beyond the Eastern bloc (Rosenberg Jonathan: 2012). From the 1950s to the 1970s however, the U.S State Department sponsored programs; sending its finest jazz musicians to the far end corners of the world (Costigliola Frank: 1984) . Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman and Dizzy Gillespie among others toured in more than 35 countries from Eastern Europe, to the Former Soviet Union, the Middle East, Asia and Africa (http://www.ebook3000.com/muisc/Jazz-Diplomacy–Promoting-America-in-the-Cold-War-Era_51802.html) in order to win the hearts and mind of people as well as to promote a positive view of America as a Democratic nation free of racism.

- “]

- Moscow, Soviet Union 1962 [Goodman Benny

Under the U.S State Department’s Office of Information and Cultural Affairs, ‘Voice of America’ offered each weak countless hours of jazz music, which became the informal hymn for many Soviets and “kept hopes of freedom alive in the darkest days of oppression in communist Czechoslovakia” pointed out Havel at the White House Millennium Evening in 2000 (http://wintersession2012.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/46566278-cultural-diplomacy.pdf). Therefore, jazz as an instrument of American cultural diplomacy, transformed the U.S -Soviets relations and also reshaped the image of democracy in the world, particularly for those living under Soviet Communism. The result of which had far more positive influential impacts than initially imagined. Jazz music successfully opened the doors towards a better understanding of ‘American Culture’ by offering a unique way of connecting with people; transcending political and language barriers. In sum, we can argue that there is no doubt that jazz diplomacy played a key role in promoting a positive image of America abroad during the Cold War.

- “]

- Cairo, Egypt 1961 [Amrstrong Louis

Bibliography

-Ambassador Cynthia P. Schneider, Cultural Diplomacy: Why It Matters, What It Can and Cannot — Do? Short Course on Culture Industries, Technologies, and Policies, Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, August 30, 2006: http://wintersession2012.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/46566278-cultural-diplomacy.pdf

-Cultural Diplomacy and The National Interest; In Search of a 21st-Century Perspective, Arts Industries Policy Forum. Available at: http://www.vanderbilt.edu/curbcenter/files/Cultural-Diplomacy-and-the-National-Interest.pdf

-Costigliola Frank: (1984), “Awkward Domination; American Political, Economic, and Cultural Relations with Europe, 1919-1933”, pp.167-182, Cornell University Press.

-Jonathan Rosenberg: America on the World Stage: Music and Twentieth-Century U.S. Foreign Relations, Diplomatic History, (Jan2012), Vol. 36 Issue 1, p65-69

-Jazz Diplomacy: Promoting America in the Cold War Era: http://www.ebook3000.com/muisc/Jazz-Diplomacy–Promoting-America-in-the-Cold-War-Era_51802.html

Cultural diplomacy is a very ambiguous term as its aims truly overlaps with the traditional public diplomacy, propaganda and nation branding (Gienow-Hecht Jessica et al.: 2010). Traditionally, it meant ‘high culture’;

implying arts, literature, theatre, dance and music but it now includes activities aimed for mass audiences called ‘popular culture’ (Mark Simon 2009). However, unlike this little puzzlement, some have define cultural diplomacy as “the deployment of a state’s culture in support of its foreign policy goals or diplomacy” (http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10063/1884/thesis.pdf?sequence=1) which implies that not only it is a matter of foreign policy, aimed to further the state’s national interests abroad but also a tool of interacting with the outside world by promoting a positive image of the country. It does that by endorsing the cultural aspect of a country; language for instance but it can also take the form of exchange between people as well as academics in order to foster mutual understanding (https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/2943/02whole.pdf?sequence=9). In the case of New Zealand’s cultural diplomacy however, the Ministry of Culture and Heritage has putted more emphasis on the practices contributing more to the advancement of their national interests rather than that enhancing mutual or international understanding (Simon Mark: 2009). However, the New Zealand’s CDIP ‘Cultural Diplomacy International Programme’, established in 2004 sought to associate the nation branding to cultural diplomacy in order to demonstrate to investors, buyers as well as international media that New Zealand, in addition to its creativity and innovation, is also a technologically advanced country (Ibid). This insight of New Zealand is largely associated to its tourism brand which promote it as a ‘clean and green’ tourist destination with a modern economy and an exciting culture which seems to very attractive for international business investment (http://www.clingendael.nl/publications/2009/20090616_cdsp_discussion_paper_114_mark.pdf). At the 2005 World Expo in Japan, New Zealand was portrayed as a great land of natural beauty as well as a creative and technologically sophisticated country during which the group ‘Kapa Haka’ of the Maori culture performed every day (Simon Mark: 2009), the purpose of which was to broaden the Japanese perceptions of New Zealand.

References

– Gienow-Hecht Jessica C.E and Donfried Mark C.: (2010), Searching for a Cultural Diplomacy”, pp.3-27 and pp. 162-175, Berghahn Books.

– MacDonald Katherine: “Expression and Emotion, Cultural Diplomacy and Nation Branding in New Zealand”, Victoria University of Wellington, March 2011. Available at: http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10063/1884/thesis.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed on the 27th March 2012.

– Simon Mark: “Discussion Papers in Diplomacy, A Greater Role for Cultural Diplomacy”, Netherlands Institute on International Relations ‘Clingendael’, April 2009. Available at: http://www.clingendael.nl/publications/2009/20090616_cdsp_discussion_paper_114_mark.pdf Accessed on the 23.03.2012

– Simon Mark: “A Comparative Study of the Cultural Diplomacy of Canada, New Zealand and India”, Research Space Auckland. Available at: https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/2943/02whole.pdf?sequence=9 Accessed on the 15th March 2012

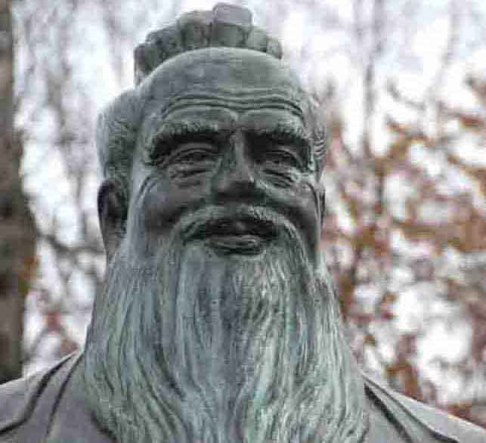

The increasing influence of American culture: popular music, movies, food, exhibitions to the Chinese young population has led the government to take actions (Edward Wong,2012). In addition to its strict policy on the importation of cultural goods, the present Chinese leader; President Hu Jintao published an astonishing essay on January 3th 2012 in the famous magazine ‘Seeking The Truth’ in which he strongly advocated “We must clearly see that international hostile forces are intensifying the strategic plot of westernizing and dividing China, and ideological and cultural fields are the focal areas of their long-term infiltration” (http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/04/world/asia/chinas-president-pushes-back-against-western-culture.html) and he added “We should deeply understand the seriousness and complexity of the ideological struggle, always sound the alarms and remain vigilant, and take forceful measures to be on guard and respond” (ibid). This clarified that the Chinese government in order to save its culture would have to both promote as well as strengthen their cultural heritage and values. However, like the French’s ‘Alliance Francaise’ and the German’s ‘Goethe-Institut’, China chose to promote its language, ‘Mandarin’ as a tool to reshape its influence worldwide as well as to advance their public diplomacy agenda (Seib, 2012). Though, its first institute was established in 2004, there are now over 320 Confucius Institutes in about 96 countries, offering a variety of activities, ranging from music, cooking, Chinese traditional medicine, their history and culture and above all, teaching Mandarin (Wey-Shen Siow M.:2011). But how successful the Confucius Institute been in transforming people’s perceptions about China? Well, for some it is nothing but a new form of the Chinese government’s propaganda. And yet for others, unlike its success in promoting both their language and culture beyond their borders, the lack of efficiency and a good degree of professionalism in some centres has led many students to drop the courses (Ibid). Thus, from this point of view, we can argue it still got a long way to go.

Bibiograpgy

- Alterman Jon B., Bliss Katherine E., Chow Edward C. et al, Chinese Soft Power and Its Implications for the United States, Competition and Cooperation in the Developing World, A Report of the CSIS Smart Power Initiative, March 2009: http://csis.org/files/media/csis/pubs/090305_mcgiffert_chinesesoftpower_web.pdfAccessed on the 8th February 2012.

- Blanchard Christopher M. et al.: Comparing Global Influence; China and U.S Diplomacy, Foreign Aid, Trade and Investment in the Developing World, CRS Report for Congress, August 15th 2008. Available at: http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL34620.pdf Accessed on the 7th February 2012

- Edward Wong: “China’s President Lashes Out at Western Culture”, The New York Times, January 3th 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/04/world/asia/chinas-president-pushes-back-against-western-culture.html Accessed on the 17th March

- Seib Philip: “Intellectual Containment and U.S.-China Relations”, posted on 2th March 2012 at 2:47om. Available at:http://www.huffingtonpost.com/philip-seib/intellectual-containment-_b_1251332.html Accessed on 15th March 2012

- Wey-Shen Siow Maria, (2011): “China’s Confucius Institutes: Crossing the

River by Feeling the Stones”, Asia Pacific Bulletin, Number 91, January 6 2011

Under the 1936 Convention for the Promotion of Inter-American Cultural Relations, the government agreed to establish a model of exchange programs as a public diplomacy tool aimed to counter Soviet influence during the Cold War (US State Department, 2005). This agenda, known as “The Fulbright Program”, first enacted in 1946 consisted of enhancing educational and cultural exchanges between the US and other countries in order to foster mutual understanding (Kennon H. Et al., 2009). Many people including students, teachers, scholars and even leaders came to the United States under the International Visitors Program to share the American cultural and experiences. This was quite effective as many world leaders among whom Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair, Afghan President Harmid Karzai and many more made their ways through this program (Ibid). Thus, it was a very successful method of engagement with foreign people for long-term connections. Nevertheless, “Since 1993, budgets have fallen by nearly 30 percent, staff has been cut my about 30% overseas and 20% in the U.S, and dozens of cultural centres, libraries and branch posts have been closed” (http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/54374.pdf). This implies that it was no longer the priority since the cultural Cold War battle was over. Does that entail that the U.S only uses their diplomacy tool in triggered situations? Well, it is not to be excluded.

References

Ambassador Cynthia P. Schneider, Cultural Diplomacy: Why It Matters, What It Can and Cannot — Do? Short Course on Culture Industries, Technologies, and Policies, Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, August 30, 2006: http://wintersession2012.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/46566278-cultural-diplomacy.pdf Accesed on the 18th March 2012

Cultural Diplomacy and The National Interest; In Search of a 21st-Century Perspective, Arts Industries Policy Forum. Available at: http://www.vanderbilt.edu/curbcenter/files/Cultural-Diplomacy-and-the-National-Interest.pdf Asseced on the 17th April 2012

Harvey B. Feigenbaum: Globalization and Cultural Diplomacy, The George Washington University, Centre for Arts and Culture, pp.2-53. Available at: http://xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/22587837/659966199/name/global+6.pdf Accessed on the 19th April 2012

Kennon H. Nakamura and Matthew C. Weed: Us Public Diplomacy: Background and Current Issues, December 18th 2009: http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R40989.pdf Accessedon the 20th April 2012

Lord’s “Voices of America” report published in 2008, highlights the need to improve American public diplomacy tools in a growing interconnected world in a bid to re-promote itself in light with its negative records in many parts of the world as well as to be better equipped to further their national interests. To achieve this goal, will be required new strategies aimed to engage, cooperate and persuade foreign audiences[1].

At first, Lord’s suggestions and recommendations seems both very convincing and rational, because it embodies concrete actions towards building better relations with foreign public by making use of the media and social networks. The stress on the importance of long-term relations, takes us back to Melissen’s (2005), “The New Public Diplomacy” who provides a good account on the relevance of ‘two-way communication’ or ‘dialogue’, the foundation of all strong relationships[2] . This implies Lord’s claim that “the views of foreign populations matter”[3], because only through this way can the United States realistically seek to adjust their reflection on the world[4]. To that end, the U.S will first need to be credible and get strong support, which may not be an easy task after the Abu Ghraib scandal and human rights violations at Guantanamo[5]. This complexity of American adaption argues Lord “when the United States is not just disliked but also distrusted, when not just our policies but our moral authority is questioned, it is politically difficult for foreign leaders to support U.S policies and potentially popular to block them”[6]. However to improve that situation, Lord strongly believes that with the support of both local and foreign audiences, the United States will be best able to understand foreign concerns and incorporate those into their public diplomacy strategy.

Nevertheless, despite having recognized the improvement of certain aspects of U.S diplomacy tools, it seems that the true underlying goal of this report is to advance U.S interests. However, Lord says “to protect America’s moral authority, as well as the trust and even power that authority conveys, our policies should be in line with our highest ideals. They must also be constructed to advance U.S interests, taking into account the full range of costs and benefits”[7]. This implies two things. First, the report seems to overestimate American traditional values in the world stage and as such fails to consider the possibility of its refutation by others. Are American values universal? Are they casted and seen by others as do Americans? Today, the United States need to discuss more than ever before the interpretations of their actions abroad and as such acknowledge the consideration of values, perceptions and opinions of foreign audience without which the struggle to better their image abroad would be insignificant.

Overall, the United States need to build strong and concrete engagement based upon genuine dialogue that recognizes differences in terms values, historical perspective and cultural tradition. To that end, they need to both recognise and accept that there are others ways to do things.

References

Lord Kristin M.: “Voices of America; U.S Public Diplomacy for the 21st Century”, November 2008, Foreign Policy at Brookings. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/rc/reports/2008/11_public_diplomacy_lord/11_public_diplomacy_lord.pdf Accessed on the 30th April 2012 at 13:12

Melissen. J. (2005): “The new public diplomacy: soft power in international relations”, Palgrave MacMillan.

Public Diplomacy:

Strengthening U.S. Engagement with the World,

A Strategic Approach for the 21st Century

Review of the Report

http://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/index.php/resources/government_reports

Overview

This report was written by the Office of the Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs of theUnited States. Mission statement of US public diplomacy is to support the achievement of US foreign policy goals and objectives, advance national interests, and enhance national security by informing and influencing foreign publics and by expanding and strengthening the relationship between the people and government of the US and citizens of the rest of the world. The report offers the Strategic Framework forUSpublic diplomacy and contains tactics, strategic imperatives and identification of objectives and challenges in US public and cultural diplomacy.

Review

Public and cultural diplomacy play increasingly important role inUSforeign policy. Expansion of American capital in the world has also negative aspects. TheUnited Stateshegemony is the fact but in some part of the world, mainly in theMiddle Eastit creates very negative reactions. After the 9/11 attacks American had to ask themselves: “Why do they hate us?” TheUnited Statesnation brand suffered very much by George W. Bush’s implementation of hard power into theUSforeign policy. For example, the invasion to Iraq, which is by Muslim considered as the second most important holly land, and involvement of media and war propaganda in spreading of pictures how American kill Muslims, including civilians, has worsened the image of the US, mainly in Arab and Muslim countries. Therefore, implementation of public and cultural diplomacy is increasingly important to improve the image of theUSabroad.

The strategic framework of the report offers a good roadmap for USpublic diplomacy. The Office of the Under Secretary of State clearly and correctly identified that to meet the challenges and seize the opportunities of the 21st century, the US need a foreign policy that uses tools and approaches to match a changing environment of the globalized world. According to Hayden, “the strategic culture behind US diplomatic institutions needed to change, in response to new threats and opportunities that challenged existing diplomatic organization – such as global terrorism, failed states, environmental security, law enforcement, and democracy promotion” (Hayden, 2012, 235).

The report correctly identifies demographic, technological and political changes in global landscape. For example, that 45% of global population is under 25 but women are 50% of population but earn only 10% of income and own 1% of property. Advanced technologies make communication almost instantaneous. It helps better and faster connect the people and it offers new opportunities for public and cultural diplomacy and it makes it more important. The report correctly identifies that traditional bilateral diplomacy can not address the full range of actors now engaged on global issues. Necessity of using increasing number of non-state actors to achieve foreign policy makes public and cultural diplomacy an important instrument of foreign policy and it helps to make it more efficient. It is necessary because as the report clearly states there are competing influences in the world such as threat of extremists who developed sophisticated media strategies,China’s growing economical importance, etc.

On the other hand, weakness of the report is that in strategic imperatives – combat violent extremism – is not clearly stated how should be smart power used in counterterrorism and how to achieve a synergetic effect by using correct foreign policies and public and cultural diplomacy.

References:

Hayden, C. (2012) The Rhetoric of Soft Power: Public Diplomacy in Global Contexts, Lexington Books,Plymouth

In reading an American Diplomat’s government report (full text in link below), I came across the different ways in which diplomats now work as a pose to many years ago. With the change in technology, the work of governments has become quicker, easier and more efficient.

As technology thrives and the world changes, diplomats have to adapt and accept these changes and learn to work with them.

Assistant Secretary of Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance, Rose Gottemoeller recently published a governmental report on this new technological change. Around the time of 1866, the transatlantic cable, which linked the United States to Europe, was complete. This new method of communication was to change the world.

This new communication method was fast and reliable, with the possible only flaw being that as it was so fast in comparison to previous methods, the time one had to sit and make a decision was vastly reduced ergo not allowing diplomats to think long enough to make informed decisions.

Technology plays a great role in public diplomacy and getting the message across the globe. From the 2009 Iranian Presidential election protests through to the Arab Spring of 2011, the use of technology has grown immensely. Protestors from both years used mobile technology to show the true events that were occurring in their cities. With growing technologies, diplomats are using social networking sites such as Twitter to interact with the public, this way the public can get up to date news about the work they are doing and should it be relevant, how the public can get involved.

When working under a prestigious role, such as a diplomat, one must always be sure to take extra security measure and be diplomatic. Online posts can be misread and deemed offensive if not explained properly, but from the lengthy Telegraph to the 21st Century technologies, how can one not be vague with a 140-character limit on Twitter?

Link to the Report:

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2007:0242:FIN:EN:PDF

Overview

The communication emphasises on the importance of culture as part of the European integration process, and the growing role of the EU in promoting its cultural richness both withinEuropeand world-wide. It consists of three main chapters addressing the contribution of the EU in the field of culture, the importance of respecting cultural diversity and promoting intercultural dialogue within the context of globalisation, and the need of a strong EU consensus for cultural cooperation. Based on extensive consultations of the Commission, the communication proposes a set of shared objectives and new working methods in achieving a European agenda for culture in today’s globalising world.

Review

The communication refers to culture as the core of human development and civilisation, and points out that even before Europe was united in an economic level, it was first and primary “a cultural entity” (p. 2). History shows that Europeans share a common cultural heritage and enjoy a rich cultural and linguistic diversity as a result of centuries of interaction, migratory flows and exchanges. While recognising the importance of fostering common understanding and cultural promotion among EU member states, globalisation with more exposure to different cultures has also called for aEurope’s identity and increased capacity in exchanging and interacting with other cultures around the world. However, there are concerns that the establishment of a European identity or the notion of unity could bring a risk of homogeny toEurope’s cultural richness and diversity, including those of the minorities (Jehan, 2012, p. 89).

Understanding the profound link between culture and development, the report then explores theUnion’s perception of culture based on its legal basis, action and policies. For instance, article 151 of the Maastricht Treaty on European Union states that “the Community shall contribute to the flowering of cultures of the member states, and foster cooperation with third countries and international organisations in the sphere of culture” (p. 4). As a result, numbers of cultural activities have been operated by the EU to enhance its cultural heritage, such as the Cultural Programme in facilitating mutual understanding and cultural exchanges at European level with a budget of 400 million EUR for 2007-2013 it can support around 300 different cultural actions per year, the Erasmus Mundus aims for academic cooperation and educational exchanges of young people, the MEDIA programme promotes the competitiveness of the European audiovisual industry, or the EU’s Digital Libraries Initiative which aims to make Europe’s cultural and scientific heritage easier to access online (European Commission: Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency).

On the other hand, with the growing EU’s presence in the world, the communication identifies the three main objectives of a EU agenda for culture: “promotion of intercultural dialogue, promotion of culture as a catalyst for growth and jobs and culture as a vital element in theUnion’s external relations” (p. 8). For instance, intercultural dialogue is seen as a constructive instrument of peace and conflict prevention, and cultural industries are an essential asset for EU’s economy as in 2004 more than 5 million people worked in the cultural sector, which was equivalent to 3.1 % of total employment population in EU-25 and contributed around 2.6 % to the EU GDP (KEA European Affairs, 2006).

Alongside addressed objectives, the Commission also suggests new working methods to enhance the EU’s cultural capacity, such as the establishment of a “Cultural Forum” for consulting cultural issues by individual artists and intellectuals, or the employment of an open method of coordination (OMC) for increased cooperation and exchange of practice between member states in the field of culture (p. 12). Nonetheless, in order to achieve these objectives and agenda, the EU will need the support and engagement of all different kind of actors and stakeholders, such as the European Parliament, member states, professional organisations, cultural institutions, foundations, non-governmental networks and involving civil societies.

Finally, it was indicated in the communication that the EU perceives itself as an example of “soft power” founded on norms and values like human rights protection, democracy, civil societies and cooperation (p. 3). Culture is seen as one of the key elements contributed to this consensus building approach. Therefore, with the development of a European agenda for culture in a globalising world, the EU is seeking to further promote its cultural richness and diversity to the world, as well as encourage more intercultural dialogue and cooperation with other countries for shared values and common understanding.

Bibliography:

Jehan, A. (2012), ‘Culture as a key factor within Western societies and a political tool for the European Union’, in Cultural Diplomacy Research,

KEA European Affairs (2006), ‘Study on the Economy of Culture inEurope’, conducted for the European Commission,

< http://www.keanet.eu/docs/contribeu2020strategy.pdf>.

The European Commission, Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency Programmes, <http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/culture/programme/about_culture_en.php>, viewed on 18 March 2012.

According to Joseph Nye, the term “soft power” refers to the ability of a country to get “other countries to want what it wants or the power of attractive ideas to set the political agenda and determine the framework of debate that shapes others’ preferences” (1990). Hence, public and cultural diplomacy -“a government’s communication with foreign audiences in order to positively influence them” (Mark, 2009, p. 12)- can be seen as a form of soft power in shaping the public attitude and international stance in order to make them accordant with a state’s national interests and strategies.

The use of public and cultural diplomacy as ‘soft power’ strategy can be demonstrated through theU.S.cultural and ideological attraction influence worldwide. The main objective of U.S. soft power policy is to increase U.S. international influence and make other countries want what America wants through its cultural values, ideological attractions and institutions. According to research, American films “occupy about 50 per cent of world screen time” (Nye, 1990), which reflectsU.S.effort in promoting the country’s cultural, ideological and democratic values through its mass media andHollywoodproductions.Washingtonalso uses educational exchanges as the means to promote understanding about theU.S., as there were “nearly 600, 000 foreign students studying atU.S.in 2003-4, double the total from two decades earlier, to become familiar withU.S.political policies, free market economy, and democratic institutions “(Walt, 2005, p. 38). Similarly,China, a rising power in the world, also seeks to develop its public and cultural diplomacy as a form of soft power to achieve its strategic goals. For instance,Chinahas been very active in promoting its culture and language through an increasing number of Confucius Institutes worldwide. However, despite the Chinese effort to use public and cultural diplomacy to shape international publics in a more favourable view of China and its worldviews, there still remain certain limitations on Chinese ‘soft power’ due to the country’s lack of democracy and negative reputation for human rights abuses and growing military ambitions.

In conclusion, public and cultural diplomacy can be seen as potential soft power instruments for states in shaping the public attitudes and conducting international agendas to achieve their interests and objectives.

Bibliography:

Mark, S. (2009), ‘A Greater Role for Cultural Diplomacy’, Clingendael Discussion Papers in Diplomacy, <http://www.clingendael.nl/publications/2009/20090616_cdsp_discussion_paper_114_mark.pdf>.

Nye, J. S. (1990), ‘Soft Power,’ in Foreign Policy, No. 80.

Walt, M. S. (2005), Taming American Power: The Global Response to U.S. Primacy,London: Norton.

Udoubtedly China’s public diplomacy is an interesting area to explore. The nation branding guru, Simon Anholt, could be proud of the methods that China used in gaining its present status without empty propaganda and marketing. Instead, it executed an “open door” policy thus attracting an immense amount of foreign investment, utilized globalization and developed a responsible foreign policy strategy. Also the greater involvement in the international organizations such as World Trade Organization or United Nations peacekeeping were smart moves on its part. All those steps granted China the position on the international arena that previously would have never be expected.

Some articles which I have come across in researching the topic suggest that China’s soft power diplomacy nowadays has at least four strands. The first one is supposed to be “quiet diplomacy” and is meant to convey the message that China as a major power is not a threat to neighbouring countries as it was commonly thought in the late 1970s when China was starting its modernisation process as led by Deng Xiaoping. He was also the one who first came up with the expression “modest comfort”- xiaokang, indicating that China aspires to create a society where everyone would be relatively well-off but national wealth and military superiority would not be priorities. Another popular term used by Chinese public diplomacy specialists appears to be the “peaceful rise“- heping jueqi, and is meant to indicate that China wants to become a major power by peaceful means and promotion of friendship with other states. Even nowadays China’s growing international power is often seen as a threat to other states, hence probably such blatant struggle to create a soft image. Another filament of China’s public outreach are the efforts to present itself as a responsible, honorable nation. This can be observed in China’s growing interest in the environmental and food-safety issues as expected of every major power. Moreover, there is also China’s cultural diplomacy, incorporated mostly in the creation of Confucius Institutes worldwide which is supposed to prove that as a major power China is not only strong in terms of economy and military but also has a significant cultural heritage and tradition. Also creation of internationally renowned exhibitions or opera performances such as for instance the “Firt Emperor” are supposed to show China’s cultural sophistication. However, the most extraordinary part of Chinese public diplomacy is probably the connection with the issue of the legitimacy of China’s socialist government and the Communist Party. It seems controversial in terms of on the one hand China’s trials to appear as modern, Westernised country, while on the other contradicting Western countries‘ assertions about the importance of democracy and human rights (an example can be its doctrine of noninterference in countries‘ internal affairs). Undoubtedly China has become very skilled when it comes to using various public diplomacy tools. In negotiations with Japan China does not hesitate to use a range of historical arguments regarding the Japanese invasion which puts Japan in an inconvenient defensive position of an aggressor and China in position of a martyr who is now back on track stronger than ever before.

On the other hand, China’s public diplomacy may appear as a shining star but as John Brown mentions in his article for the Huffington Post, in practice it is not so dazzling anymore. He gives an example of the website of the Chinese embassy in Washington which is very rarely accessible and it is almost impossible to find its phone number online. Even if the number is found, the line is always busy thus, the access to embassy is severely limited. Brown indicates that the Embassy employees only advertise what the headquarters want on paper, just to please their bosses rather than truly engage with the host country’s natives. Although he’s based his opinion on the performance of just one embassy, if the “fortress embassy” scenario is real also in other countries, it may be a major flaw in China’s strategy to be seen as a major power.

Although the Cold War remained cold throughout the forty years of arms race, the ideological battle between the United States and the Soviet Union never ceased. Hence, the transmission of values, ideas and images became key elements in the struggle between the superpowers (Davis: 2003, 199).

Many suggestions have been made as to what caused the collapse of communism but the importance should not be underestimated that ‘’knowledge about American culture, whether acquired by participating in our exchange programs, attending cultural presentations, or simply listening to Voice of America, contributed to the death of communism’ (Finn: 2003, 15). Hence, there are important lessons to learn from cultural diplomacy during the Cold War. Cultural diplomacy became an incorporated and essential part of US foreign policy as both the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the newly established United States Information Agency (USIA) were engaged in cultural activities abroad.

As a result of the agreement between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on Exchanges in the Cultural, Technical, and Educational Fields from 1958, exhibitions became a common method of disseminating the values of each camp as in the case of simultaneous exhibitions in New York and Moscow in 1959. In Sokolniki Park in Moscow, a six-week long display of American consumer goods and images induced great curiosity among the Russians and allegedly ‘offered a greater return than any single Cold War initiative since the Marshall Plan.’ (Davies: 2003, 210) Importantly, such images shed light on all the things which were unavailable in the Soviet Union and thereby worked to discredit the Soviet regime.

Another important aspect of this effort was the involvement of non-state actors. The Russian-speaking Americans in charge of many of these exhibitions provided a crucial opportunity to portray American values in a credible manner. As James Critchlow points out, often these were college students who became cultural ambassadors due to the enormous interest from attending Russians asking questions unrelated to the exhibition itself but about political and social issues in the US (Critchlow: 2004, 79). More generally, non-state actors, whether state-sponsored or not, have played vital roles in the positive portrayal of American culture as evident in the concept of Jazz diplomacy. Music tends to transcend borders and political differences and instead communicates a common interest between otherwise conflicting parties. The US government’s initiative, originally proposed by Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, to send the jazz trumpeter, Dizzy Gillespie on world tours became strikingly popular and when the radio station, Voice of America (VOA) inaugurated the program ‘Music, U.S.A’ primarily airing Jazz, the audience increased dramatically. In an interview, Louis Armstrong concluded that jazz bridged the gap between capitalism and communism (Bratton: 1998, 16).

With the war on terror, the US has found itself in a somewhat similar ideological position which emphasises the problems of discontinuing the USIA after the Cold War. Cultural diplomacy still plays an essential role in maintaining and improving long-term relationships but it cannot be applied on an ad hoc basis, something the US will have to acknowledge in today’s security environment.

However, there are still important differences in the application of various cultural strategies since a CIA-sponsored cultural diplomacy initiative would be highly inappropriate today in terms of credibility. Nevertheless, the main point is that cultural diplomacy has played and should play an essential role in foreign policy to bridge cultural gaps and political differences.

Bibliography

Bratton, E., ‘Jazz Diplomacy and the Cold War’, New Crisis, Vol. 105, No. 1, 1998, p. 16 (15-19)

Critchlow, J., ‘Public Diplomacy during the Cold War: The Record and Its Implications’, Journal of Cold War Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1, Winter 2004, pp. 75–89.

Davies, N.G., ‘The Logic of Soviet Diplomacy’, Diplomatic History, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2003, pp. 193-214.

Finn, H.K., ‘The Case for Cultural Diplomacy: Engaging Foreign Audiences’, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 82, No. 6, 2003, pp. 15-20.

The concept of ‘nation branding’ has a British root, as the term was first time coined by British policy advisor Simon Anholt in 1996 as ‘the combinations of the country-of-origin studies, which incorporate political, cultural, sociological and historical approaches to national identity’. In comparison, Wally Olins states that countries have always branded and re-branded themselves and it is just a new term for image management (2002, p. 241). Similarly, nation branding can be seen as “branding and marketing communications techniques to promote a nation’s images” (Fan, 2006, p. 6). However, it is important to distinguish between the concept of ‘nation branding’ (people identities and culture) and ‘country branding’ which aims at specific locations, such as destination branding with primary focus on tourism (Widler, 2007, p. 144). Generally, it can be argued that image promotion is the ultimate goal of nation branding, and effective branding would require a long-term consistent strategy.

Nation branding refers to nation’s image as the way a nation’s people want the world to understand what is most central about their nation. Nation’s image is defined by foreign publics and their perceptions are often influenced by stereotyping, media coverage or their personal experience of the nation state. For instance, branding methods were used by some transitional countries, such as Eastern European post-communist governments as the means to distance the country from the old economic or political system in response for membership in international organisations. The relationship between national identity, nation branding and nation’s image can be summarised as below:

Source: Branding the Nation: Towards a Better Understanding, Ying Fan (2009)

On the other hand, there are certain conceptual similarities and differences between nation branding and public diplomacy. For instance, both refer to communication and attraction as the means to achieve strategic goals, and therefore they are both instruments of soft power. It is argued that nation branding aims at both domestic and foreign publics as equally important targets. As Anholt argues that the primary role of domestic citizens is to ‘live the brand’ and perform as brand ambassadors, and nation branding thereby can be seen as a common sense of objective and national pride (2002, p. 234). In terms of foreign audiences, while public diplomacy tends to target a particular group of cultural or political elites, nation branding targets mass audiences, which gives it a broader influence towards the public in a target nation and more ‘public’ than public diplomacy (Szondi, 2008, p. 12).

Furthermore, according to Szondi there are five different possible views on the relationship between public diplomacy, whether these concepts are unrelated, the same concepts, public diplomacy is part of nation branding and vice versa, or they are distinct but overlapping concepts (Szondi, 2008, pp. 14-29). For instance, Anholt considered public diplomacy as part of nation branding reflecting in his Brand Hexagon, in which the core national brand strategy or ‘competitive identity’ is based on the management of all elements like public diplomacy, tourism, investment, and export promotion (2007, p. 3).

Nonetheless, the most possibly accepted view is that public diplomacy and nation branding are distinct concepts but they do share some common characteristics. As Jan Melissen claims that they are ‘sisters under the skin’ with both striving for image promotion, building national identity, culture and values as the key common objectives (2005). Based on this approach, it can be argued that both public diplomacy and nation branding focus on relationship building, either with regard to a strategic self presentation of a nation or two-way network communications among countries in international relations (Szondi, 2008, p. 28).

In conclusion, nation branding and public diplomacy are both dynamic processes, which reflect the ability of a country to build and manage its attractiveness to achieve its strategic goals. Nevertheless, effective branding would require a coherent long-term strategy by states with adequate financial and human resources in order to create a better image and reputation of themselves in the world.

Various views on nation branding:

Simon Anholt:

– Nation branding Master class: http://www.simonanholt.com/Masterclasses/masterclasses-the-commissioned-masterclass.aspx

– Place Branding and Public Diplomacy Journal (edited by Anholt): http://www.palgrave-journals.com/pb/journal/v8/n1/index.html

Wally Olins:

– ‘How to Brand’ http://www.wallyolins.com/includes/how_to_brand_a_nation.pdf

– Video: ‘The Nation and the Brand and the Nation as a Brand’, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ta9Es6MNrbI

‘Nation Branding in A Globalized World’- A Video Lecture by Uffe Andreasen (former Danish Ambassador and Permanent Delegate to UNESCO), 2010, available online at http://www.culturaldiplomacy.org/index.php?nation-nranding-videos-main&highlight=nation%20brand

Bibliography:

Anholt, S. (2002), ‘Foreword’, in Journal of Brand Management 9 (4-5), pp. 229-2239.

Anholt, S. (2007), Competitive Identity: The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions,Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fan, Y. (2006), ‘Nation Branding: What is being Branded?’, in Journal of Vacation Marketing, Vol. 12, Issue 1, pp. 5-14.

Fan, Y. (2009), Branding the Nation: Towards a Better Understanding,

<http://bura.brunel.ac.uk/bitstream/2438/3496/1/NB%20Towards%20a%20better%20understanding.pdf>.

Melissen, J. (2005), The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations,Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Olins, W. (2002), ‘Branding the Nation’, in Journal of Brand Management 9, pp. 241-248.

Szondi, G. (2008), ‘Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding: Conceptual Similarities and Differences’, in Clingendael Discussion Paper in Diplomacy, No. 112,

<http://www.clingendael.nl/publications/2008/20081022_pap_in_dip_nation_branding.pdf>.

Widler, J. (2007), ‘Nation Branding: With Pride against Prejudice’, in Journal of Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 3, pp. 144-150.

With nearly 2.5 billion internet users (http://www.newmediatrendwatch.com/world-overview/34-world-usage-patterns-and-demographics ) and 6 billion mobile phone subscriptions worldwide (http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/), the democratization of communications technology has effectively removed any sort of monopoly on the dissemination of messages concerning the national interest of governments. Consequently, this has had a great impact on the way that the tools of public and cultural diplomacy are being used and assessed, as the key to effectively engaging with foreign publics may well lie outside the reach of our traditional and institutionalised actors.

Although the argument asserting that states remain the predominant actors in the international system may still be valid, the diffusion of power in terms of successfully projecting the message with a content of credibility is also become increasingly evident (Wang, 2006: 35). Accordingly, today many political issues may be more appropriately addressed at the local or global level.

The overriding purpose of public diplomacy is to promote a positive image and reputation of the nation-state to influence foreign publics and governments by building lasting relationships in a way which furthers the national interest of the that state. However, particularly for the United States, public diplomacy efforts have occurred in an often ad hoc manner whenever it has been deemed necessary thereby reflecting only American interests. But as Zatepilina points out, successful communication goes beyond the listening two-way kind and endeavour to recognise the interests of the target foreign public, what she calls strategic communication. In this respect, non-state actors play a crucial role because, unlike governments and diplomats, they do not necessarily arrive with the purpose of imposing a certain agenda as many NGOs are starting to understand. Rather, they enjoy the ability to establish the personal relations which ought to be the foundation on which true public diplomacy is built (Zatepilina, 2009: 157). A recurring theme in the debates about public and cultural diplomacy is that of credibility and little doubt remains that detachment from the agendas of governments ad a great amount of that.

Some have regarded government-sponsored NGOs an unfortunate extension of US policies resulting in suspicion. On the other hand, as Zatepilina emphasises, when there is disagreement between the government and an NGO as was the case with the implementation of an anti-terrorist legislation in Kenya requested by the US embassy, the US ought to embrace this disagreement as a representative to the democratic values it is in fact aiming to promote (ibid: 161). Zatepilina suggests that the US government should incorporate examples of successful into its messages, but this is where I partly disagree. I believe that the credibility of non-state actors derive exactly from the fact that their diplomatic potential and achievements have not yet been institutionalised. Once non-state actors are perceived as diplomats both by their own and other governments and publics, the latitude they currently enjoy might disappear. To a large extent, the use of NGOs to promote a good reputation is ideal but I am also inclined to suggest that countries like the US are better off educating its own public on how to nurture good relations in terms of appropriate behaviour and enthusiastic engagement abroad such as the ‘World Citizens’ Guides’ proposed by BDA but simultaneously be careful not to use strong labels (Pigman, 2008: 98).

Another interesting aspect of citizen diplomacy is represented in the ‘outsourcing of diplomatic representation’ or ‘private diplomacy’ (ibid: 94). This can involve both firms with expertise on public relations which, detached from political incentives, can propose a well-balanced ‘business plan’ encompassing the right analysis and strategies which may indeed value the interest of foreign publics significantly more than a similar plan developed by for instance the US State Department would have.

Celebrity diplomacy is another strand of the diplomatic practice that has gained prominence in the debate about what constitutes a legitimate actor within the field. A growing number of celebrities such as Bono, Angelina Jolie and George Clooney have successfully raised awareness of issues such as AIDS, refugees and human rights and have often produced impressive results in placing these on the policy agendas of German Chancellor Angela Merkel and US President Barack Obama (http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/from-alister-to-aid-worker-does-celebrity-diplomacy-really-work-1365946.html). Celebrities are, like other non-state actors, detached from the ‘national interest curse’ which tends to remove the credibility of traditional diplomats.

However, celebrity style diplomacy has been subject to criticism on grounds of selectivity and a lack of appreciation of the diversity of the issues they elevate as voices in the global south tend to disappear in the marketplace of attention-demanding statements. For instance, the call for increased aid is in itself controversial since the effectiveness of aid is by no means an undisputed matter.

Despite the criticism, celebrity diplomacy ought not to be dismissed. Rather, it is a learning process where faulty approaches must be remedied. Angelina Jolie is one example of a celebrity who comprehends the importance of integrity in her decision to hire an advisor on international affairs enabling her to adopt a more comprehensive view of the projects on which she embarks. She has been less vocal than many other celebrities and has instead let her actions speak (ibid).

A recurring theme in the debate about public diplomacy has been that of credibility. Evidently, non-state actors have occurred as a viable alternative in the diplomatic field where they appear more legitimate due to the fact that they have not yet been institutionalised and hence are exempt from the ‘national interest curse’. In my view, it is important that the distance between governments and non-state actors is maintained although more appreciation of the significance of the latter by the former is essential. Therefore, the role that each actor plays must be more specifically defined so that all kinds of diplomats understand their place in the increasingly blurry field of public diplomacy.

Bibliography

Pigman, G. And Deos, A., ‘Consuls for Hire: Private Actors, Public Diplomacy’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, Vol. 4, no. 1, 2008

Wang, J., ‘Localising Public Diplomacy: The Role of Sub-National Actors in Nation Branding’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2006

Zatepilina, O., ‘Non-State Ambassadors: NGOs’ Contribution to America’s Public Diplomacy’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2009

International Telecommunication Union, http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/

New Media Trend Watch, http://www.newmediatrendwatch.com/world-overview/34-world-usage-patterns-and-demographics

The Independent, ‘From A-lister to Aid worker: Does celebrity diplomacy really work?’, 17 January 2009, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/from-alister-to-aid-worker-does-celebrity-diplomacy-really-work-1365946.html

I have decided to post about profile of public diplomacy in the post-communist countries as I consider it quite interesting to observe how all those states, with publics and governments still strongly influenced by previous political regimes, started only recently developing their public diplomacy strategies. I would like to focus mostly on Poland which for me remains the most curious case of brand building in central Europe with the increased ambitions of catching up with Western Europe but still not taking full advantage of its potential and sticking to idle ideas.